Battle for growth: policymakers versus geopolitics

By Graham Bishop, Investment Director at Heartwood Investment Management, the asset management arm of Handelsbanken in the UK

While as a house, we feel optimistic about the outlook for financial markets, we are well aware that the current, long running period of economic expansion is delicately poised. Stall speed, the rate of growth necessary to keep things at least on an even keel, is not far away. Arguably, we are one material ‘shock’ away from entering into a downward spiral, or a global growth recession. How did the world get to this point?

The main protagonists include a US-China trade war, US monetary tightening and a fading of the stimulus which helped the global economy in 2016-17. Brexit uncertainty surely hasn’t helped in the UK, but globally this is something of a side issue. What matters most, though, is that all these headwinds have coincided with a period of economic expansion that is around ten years old, and maturing in more ways than one.

If you’ve read this far, you could be forgiven for feeling pessimistic. Fortunately, there are plenty of positives that likely mean the global economic show stays on the road for the time being. In essence, we don’t think a global growth recession will be a feature in 2020, due to support from central banks (monetary easing), from governments (fiscal easing), and from negotiators keen to put an end to geopolitical uncertainty (trade wars and Brexit). These statements are, of course, judgement calls, but we have conviction in them at present. Things can (and do) change, and we will be monitoring key issues closely. Let’s examine each below.

Central banks: will they remain accommodative?

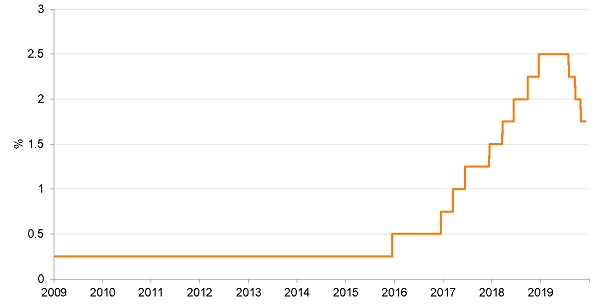

The central banks have certainly implied that they will. Chairman Powell of the US Federal Reserve (Fed) is intent on sustaining the economic expansion. That is why the Fed reduced interest rates three times in 2019 (in July, September and October), with possibly more to follow. This was a big reversal of the rate hiking cycle that was in place from 2015 to 2018. Moreover, the Fed is once again increasing the size of its balance sheet, which involves purchasing government debt in the secondary market in an effort to keep interest rates under control. This reduces the cost of issuing debt in US dollars, and with the US dollar still the world’s reserve currency, this is good news for global issuers of US dollar debt, including swathes of emerging markets as well as the US itself.

Aside from the Fed, a great many other central banks have followed suit and reduced interest rates. Currently, about half of the fifty or so central banks that can really impact investment markets are actively easing financial conditions; fewer than ten are still increasing rates. Ultimately, this central bank stimulus should act as a tailwind to global growth. In some ways, we view this situation as similar to the events of 1994-96, when the Fed reversed its prior interest rate hiking regime just in time. The ‘insurance’ cuts that ensued paved the way for a longer economic cycle and strong stock market gains.

The Fed has reduced interest rates at three consecutive policy meetings

US Federal Reserve target rate

Source: Macrobond, Bloomberg

Governments: will they step up in earnest?

Governments’ tax and spending plans in recent years have been off the front page, as central bankers have dominated the headlines with unconventional policy manoeuvres. But things are changing. Central bankers seem increasingly keen for governments to enact structural reform and offer financial support to the economy, as the efficacy of interest rate cuts and/or quantitative easing (QE) starts to fade.

Indeed, we are already seeing tentative signs that their persuasive efforts are not in vain. Germany is considering relaxing its typically inflexible approach to government spending, even if this is largely centred on causes related to climate change. Japan has also announced a public spending boost of $121bn, seeking to offset the economic effects of relatively recent natural disasters. Even in the UK, after years of austerity, both main political parties are proposing more respite. President Trump would surely like to follow suit, but the government tax cuts of 2017 have already taken the US budget deficit to unpalatable levels. China, in its own way, has also been relaxing the fiscal purse strings. Some of this may be due to offsetting trade tariff effects, but something is better than nothing.

In aggregate, therefore, it would seem that the world is already starting to experience a boost from government spending policies. The ‘fiscal impulse’, as economists tend to describe it, has been building across developed and emerging economies of late. There is a good chance this builds further – potentially good news for global growth, and inflation.

Trade wars and Brexit: is resolution in sight?

The aspect of the global economy which is trickiest to forecast is how trade negotiations will proceed from here. This is hardly surprising, given the unpredictability of the central character, President Trump. Our belief, however, is that as the November 2020 US Presidential election draws near, a strong economy characterised by low unemployment rates would all but secure his re-election. A full blown trade war with China or Europe would not be helpful in this regard. As such, it would serve Mr Trump’s interests for his team to persevere in his trade negotiations with China.

At the time of writing, this looks to be underway. A trade deal would be beneficial for the global economy mainly because it would lessen the fog of uncertainty that is curtailing corporate confidence, and thus capital expenditure. Were business investment growth to accelerate, we believe it would act as a powerful driving force for growth and one that has been absent for several years.

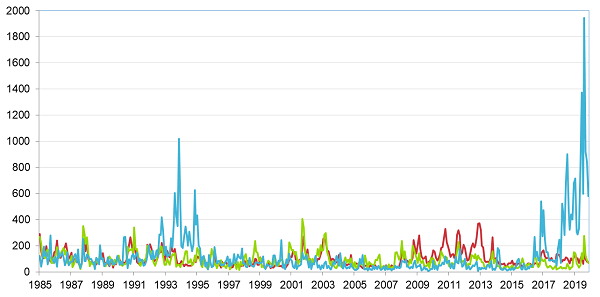

High levels of uncertainty have hampered business confidence

US economic policy uncertainty

Source: Macrobond

The poster child for what uncertainty can do to an economy is, of course, the UK and the ongoing Brexit saga. In December’s general election, the UK electorate gave Prime Minister Johnson’s Conservative Party a mandate to govern, and a mandate for Brexit. Indeed, Brexit has dominated and redrawn the political map during this election, ultimately giving Johnson a relatively free hand – in the UK parliament at least – to pass his version of Brexit. Some of the UK's political uncertainty could therefore be eased soon, potentially offering near-term gains as long-delayed spending decisions are finally enacted at a household and business level. The sugar rush from this possible spur of investment and growth would likely fade at some point – perhaps by the end of 2020/2021 – but for now this is set to be good news for business and consumer confidence in the UK.

What does this mean for investors?

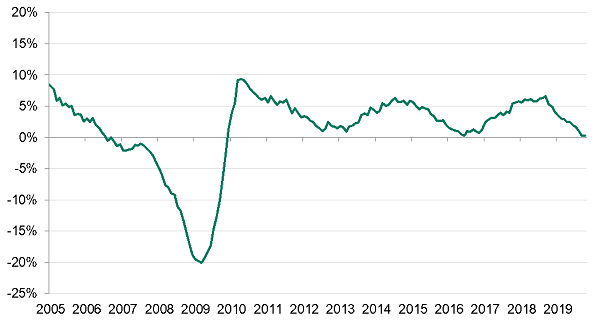

The world economy has experienced a series of ‘mini cycles’ within a broader period of expansion over the past ten years. Despite plenty of reasons to be gloomy, as we ourselves felt only a year ago, it seems that efforts are now underway to sustain the global economic expansion. Beyond 2020, it’s not easy to say whether 2021 or thereafter will be when the music stops playing, but for now we are moderately optimistic.

The global economy has played host to a series of "mini cycles" over the past decade

Leading indicators of the US business cycle

Source: Macrobond, Bloomberg

Found this useful?

Take a complimentary trial of the FOW Marketing Intelligence Platform – the comprehensive source of news and analysis across the buy- and sell- side.

Gain access to:

- A single source of in-depth news, insight and analysis across Asset Management, Securities Finance, Custody, Fund Services and Derivatives

- Our interactive database, optimized to enable you to summarise data and build graphs outlining market activity

- Exclusive whitepapers, supplements and industry analysis curated and published by Futures & Options World

- Breaking news, daily and weekly alerts on the markets most relevant to you