Are Brains Blocking Business Change?

Written by Dr Patrick McCreesh of Simatree working alongside Pirum

An organisation is only as good as its ability to evolve in today’s fast-changing environment. For most organisations this ability is directly linked to the ability of business leaders to understand change and help people adjust. An organisation changes one person at a time, but why do some people change and others fail to evolve? The answer is in attachment behaviour – a mechanism through which individuals lean on tangible and intangible objects for security. This article describes how attachment impacts change in institutions and how leaders can re-think managing change through the lens of attachment.

Financial institutions need to evolve. Some changes are mandatory, such as emerging global regulatory led directives. Market forces drive other changes, such as mergers and acquisitions or the outsourcing/offshoring of back office operations. Disruptive technologies will bring still more changes – such as block chain, machine learning, and artificial intelligence – prompting the need for robust digital transformation across the industry. Each of these potential changes brings significant opportunity, while failure to evolve presents an existential threat to the business.

Despite these constant and growing pressures, in reality institutions often fail to effectively change. Gartner reports that only 34 percent of transformational efforts are clear successes, while nearly half are clear failures. The biggest impediment to successful change is not the ability to make the “technical change” (e.g., new regulations or new technology), but rather to get people to take their part in adopting new behaviour. Nearly half of CIOs across industries blame culture, not technology, for the failure of modern digital efforts. At a recent RMA conference, a plurality of 41 percent of participants reported that “resistance to change” is the top impediment to successful transformation.

Given the evolving ecosystem most organisations are compelled to invest in change management. Most changes require shifts in employee behaviour and many complex transformations may require all employees to make a change in their job. Change management helps, but it doesn’t always mitigate resistance.

If changing is so important and organisations already invest significantly in change management, why don’t people change? Researchers suggest that people lack the desire to change based on misunderstanding of intent or insufficient incentives. There is a sense that more energy or resources will precipitate a reliable shift in behaviour. We offer that there is something deeper at play - each change breaks a psychological attachment that employees have in the workplace and these breaks create a sense of loss amongst employees.

Attachments in the Workplace

Attachments are not casual connections that employees have, these are deep neurological and biological processes that help people navigate a social environment, such as a workplace. Attachments are rooted in the early days of our lives. As we formed our first understanding of ourselves as separate from our parents, we found ways of coping with the loss of the original attachment we had to our parents. We found ways of connecting with other people (non-parental caretakers) or objects (blankets, pacifiers, stuffed animals) that provided a comfort to our early existence.

As we grew into young adults, we formed new bonds through religion, sport, school, or perhaps civic/community organisations that created a familiar connection. These connections were to people, role models, or the ideas that created a sense of belonging and comfort. Then, as we grew into adults, these attachments shifted to the workplace where we found roles, smaller subgroups of colleagues, office locations, technologies or even physical objects (think of Gareth’s/Dwight’s stapler in “The Office”) that became a part of our identity and comfort in the workplace.

These attachments are good for people and they are good for organisational health. Attachments explain why some people connect to the mission of the organisation, the culture of the organisation, or even individual leaders. However, these attachments can emerge as a significant challenge when an organisation wants, or needs, to change.

Attachments During Change

When an organisation introduces a change, it will inherently cause some individuals to feel a sense of discomfort. The discomfort is a form of anaclitic depression, similar to what young children feel when separated from their mothers. In short, it is a sense of loss. Even if the change is as simple as an upgrade to the latest version of Windows, a familiar shortcut or tool bar will change and make them feel like they have lost something.

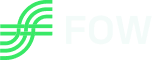

This sense of loss results in a series of negative behaviours that can be observed by leaders and managers. Individuals may feel frustration, apprehension, rejection of their environment, a slowing of personal development, refusal to participate, or withdrawal. At the individual level, these symptoms seem more harmful to the individual than to the company.

However, as many individuals start to feel the same symptoms, they aggregate to a much deeper problem. The organisational equivalent emerges in business terms, including: a loss of productivity, low morale, increased conflict, loss of motivation, absenteeism and turnover. Often time, leaders will see these symptoms in their workplace and label it resistance, but the tension they feel is this break in attachment yielding some of the individual or organisational symptoms.

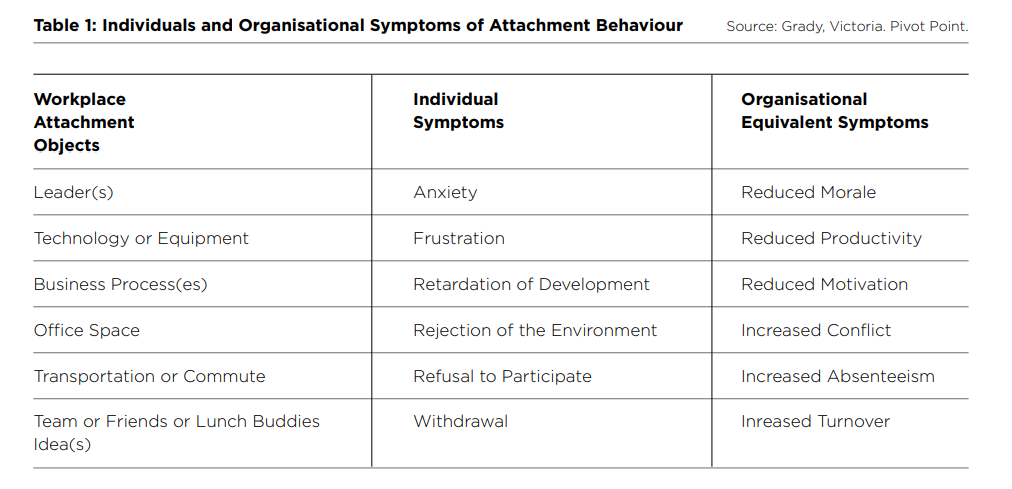

The financial industry is facing a series of significant changes right now. Let’s play out how attachment can impact each of these changes. There are three dimensions to consider when assessing these changes. First, what control do leaders have over the change? Is it being forced from an outside entity or is the change driven by internal desires? Second, as mentioned before, how much of the change’s success is predicated on a shift in people’s behaviour? Third, what are the potential attachment symptoms that will emerge due to the change?

While the list is by no means exhaustive of the changes impacting the industry, it is reflective of the changes facing many institutions. Table 2 explores these six areas and describes how each change might reveal tensions to leaders.

It is clear that most changes have a great deal of leadership control AND require people to change their behaviour. This is good for organisations that choose to take control over their attachment challenges. It means that leaders can engage and proactively address the symptoms outlined here.

How to Address Attachments

Attachment theory provides a strong understanding of why individuals resist change. They are not lazy, wrong, or bad people; they have a deep psychological connection to some aspect of the organisation (which is good), but that connection is challenged by change.

In order to address attachments during change, leaders can take three practical steps:

1. Acknowledge the Sense of Loss – Leaders need to demonstrate empathy for the impact the change will have on employees. More importantly, they need to incentivise the behaviour of middle managers to ensure they also demonstrate empathy with employees. Even a strong empathetic organisational leader can lose traction when a frontline leader dismisses employee feelings.

2. Understand (and Monitor) the Attachment Impacts – The symptoms described above are not abstract. They are measurable through employee engagement surveys and change readiness assessments. Leaders can both understand the nature of organisational attachments prior to a change initiative and monitor shifts in attachment through the change.

3. Provide a Transitional Object – As individuals separate from attachments, they can be supported with transitional objects that are physical support mechanisms. As children, these may have been blankets or toys, but as adults they are physical reminders of the change that reinforce new behaviours. These might include publicly posted signs, branded giveaways, or developmental “toys.”

As financial service institutions continue to evolve to meet the needs of their customers and shareholders, they will need their employees to evolve too. Each change brings the opportunity to advance the organisation, but at a risk of impacting the attachment of an employee. By understanding these attachments and recognising the symptoms of attachments, rather than meeting with resistance, leaders can evolve their organisations with a culture of change support.

Case Study: A Global Merger Creates Different Local Attachments

Financial Service institutions continue to consolidate through mergers and acquisitions. These complex change management exercises require a deep understanding of the attachments within and across two separate entities. It is important for these businesses to understand how best to leverage attachments within an organisation to maximise the value of the combined entity without disrupting current operations. In a global institution, these attachments can vary not only across the two companies, but also across different locations.

In a case study I researched, two employees had different experiences with the rollout of the merger and the management of attachments. The experience was relatively smooth for Michael. “It was certainly a challenging time, there seemed like an insurmountable amount of work to do to get the two firms and their processes knitted together.” Despite the challenge, Michael saw leadership provide a clear strategy and direction for the merger then felt open communication throughout the process. He notes “The management team did a great job in keeping the team informed of plans and developments and it felt very much like a team pulling in the same direction.”

There was a great deal of respect for the leadership and this attachment was used to ease the transition. He notes, “I saw that people had pride in doing what was needed because their leaders displayed pride.” The leadership also used incentives to ensure people felt supported. Mechanisms like retention bonuses, happy hours and even iPods were provided as potential transitional objects to support employees through the merger. As Michael concludes, “For me, this period of extreme change was seen as a positive move and I think that the attitude, energy and honesty of the management team was the main reason for this being perceived as a positive time.”

Donna had a very different experience. She worked in a different location where the merger was under a different leadership team. The new organisation moved the physical place of work to a new location with an hour commute (or more) from the current office. Donna’s reaction: “This was a negative lifestyle change for the majority of employees. Some even relocated their homes/families to be closer to the new office.” She notes that, “Once the move was made, some employees from the buying side seemed ‘unfriendly’ and gave off a vibe of ‘Us versus Them.’”

Donna saw broken attachments in her organisation with employees left to fend for themselves. She did not see an active leadership team, “They could have used a more top-down approach to helping employees integrate, as at times employees may have felt a ‘sink or swim’ attitude.” With minimal attachments, a situation like this would have demanded incentives or strong transitional objects to help support people through the change. However, instead of a cohesive management team providing equal incentives and support, it was individualised to the manager.

Whereas Michael saw a smooth transition leveraging attachments, Donna saw chaos through broken attachments. Michael felt a leadership team come together with a commitment to build a new organisation. Leaders provided the vision and culture to lead the team forward, using attachments to leadership as a driver of change - they made themselves the transitional object. For Donna however, many potential attachments were broken, as changes in location, leadership, and roles were all happening simultaneously. While there were small attempts to support employees, these were nothing compared to the broken attachments.

Found this useful?

Take a complimentary trial of the FOW Marketing Intelligence Platform – the comprehensive source of news and analysis across the buy- and sell- side.

Gain access to:

- A single source of in-depth news, insight and analysis across Asset Management, Securities Finance, Custody, Fund Services and Derivatives

- Our interactive database, optimized to enable you to summarise data and build graphs outlining market activity

- Exclusive whitepapers, supplements and industry analysis curated and published by Futures & Options World

- Breaking news, daily and weekly alerts on the markets most relevant to you